Those who know me know that I’m a theology nut. I love studying theology, and doctrine, and stuff like that. Kinda’ nerdy of me, I admit, but it has enriched my relationship with Jesus immeasurably.

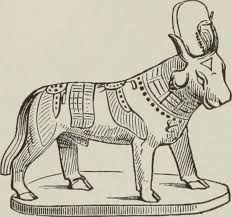

But for the past several weeks I have been chewing on the idea of how we can make our theology an idol. I don’t mean by that, of course, that we make God (as revealed in God the Father, Jesus the Son, and the Holy Spirit) an idol, as that is impossible — God is the only proper object of our worship and devotion. But the things we believe about God — and scripture, and worship, and baptism, and predestination, and end times, ad infinitum — have the potential, perhaps, to become idols in themselves.

Jesus summed up the Old Testament law as follows: Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength, and love your neighbor as yourself. But notice what he says immediately after: “There is no other commandment greater than these.” (Mark 12: 29-31) In other words, the command to love God and love your neighbor is greater than the command to dunk or sprinkle during baptism, the command to use instruments in worship (or not), the command to believe (or not) in unconditional election, and so forth. Now, I am not saying that these things are not important. I’m simply saying that these things can become idols. And idols, by definition, transgress the greatest commandment: to love God with all our heart, soul, mind and strength. And they can quite easily also cause us to dismiss those who do not agree to the letter with our theology, leading us to violate the second greatest commandment: to love our neighbor as ourselves.

I thought of all this when I was reading Gordon Fee’s commentary on First Corinthians, specifically his brief summary at the end of chapters 1-3. Here is the excerpt which particularly pricked my heart:

The Corinthian error is an easy one to repeat. Not only do most of us have normal tendencies to turn natural preferences into exclusive ones, but in our fallenness we also tend to consider ourselves “wise” enough to inform God through whom he may minister to his people. Our slogans take the form of “I am of the Presbyterians,” or “of the Pentecostals,” or “of the Roman Catholics.” Or they might take ideological forms: “I am of the liberals,” or “of the evangelicals,” or “of the fundamentalists.” And these are also used as weapons: “Oh, he’s a fundamentalist, you know.” Which means that we no longer need to listen to him, since his ideology has determined his overall value as one who speaks in God’s behalf. It is hardly possible in a day like ours that one will not have denominational, theological, or ideological preferences. The difficulty lies in our allowing that it might really be true that “all things are ours,” including those whom we think God would do better to be without. But God is full of surprises’ and the Eternal One may choose to minister to us from the least expected sources, if we were but more truly “in Christ” and therefore free in him to learn and to love.

This does not mean that one should not be discriminating; after all, Paul has no patience for the teaching in Corinth which had abandoned the pure gospel of Christ. But to be “of Christ” is also to be free from the tyrannies of one’s own narrowness, free to learn even from those with whom one may disagree.

Fee, Gordon D., The First Epistle to the Corinthians, Revised Edition ( TNICNT; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2014) 168-169.

Fee wrote those words in 2014 (perhaps earlier), and few can argue that theological exclusivity and ideology has, much to our detriment, made substantial inroads in the Church in the last 10 years. Truly, in many cases we have become enslaved to the tyranny of our own narrowness.

Paul also said in First Corinthians Chapter 2: “For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified.”

Good words. Words to live by.